Eye-Catching New MFAH Show Tackles Racism, Creativity — and 35 Years of One South African Artist's Work

William Kentridge in his Johannesburg studio in 2016

NOW ON VIEW at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston is William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows. Organized in collaboration with The Broad, Los Angeles, the exhibition encapsulates 35 years of Kentridge’s artistic output, and features over 80 thematically interconnected works, including charcoal drawings (you’ve never seen so many gradations of black, white and gray), stop-animation films, and bizarre assemblages of gears, camera lenses, and megaphones.

Born in 1955 in Johannesburg, Kentridge uses art to explore the colonial roots and horrors of systemic racism and apartheid and the current socio-political realities of South Africa since it held its first democratic elections in 1994. He also investigates (and maybe defends?) the very nature of creativity, and the tools and actions applied in art making.

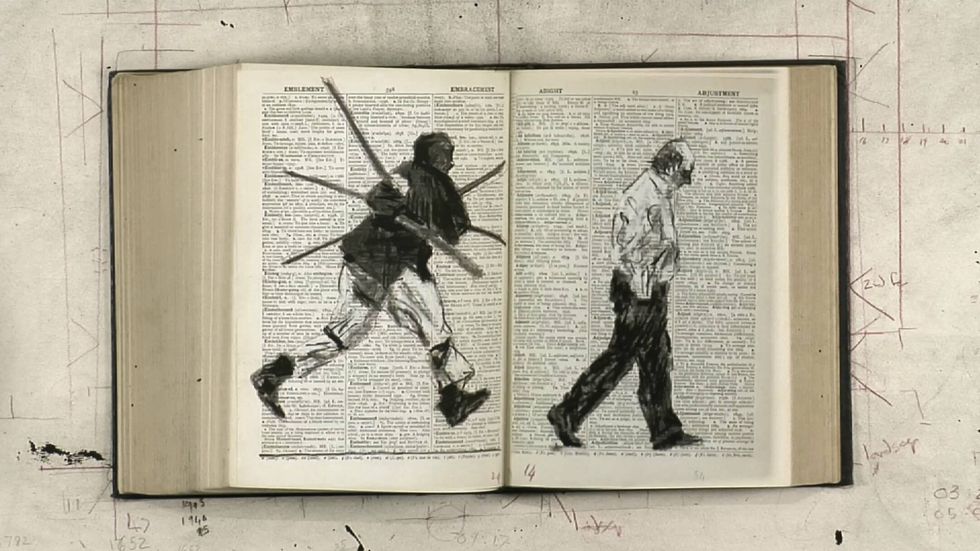

'Stereoscope,' 1999

'Second-hand Reading,' 2013

'7 Fragments for Georges Méliès,' installation view, 2003

In “7 Fragments for Georges Méliès” — an immersive installation of nine simultaneously projected films, many starring Kentridge in the flesh — Kentridge brings the viewer deep into his studio, a sacred space where creative vision is born out of imaginative free association and (as any working artist will attest) repetitive physical activity. In one film, Kentridge’s wife appears behind him, nude, looking like an apparition in a silent movie but also recognizable as a life partner and a radiant source of archetypical feminine energy.

Without a doubt, In Praise of Shadows is the most provocative and historically acute exhibition the MFAH has hosted since the controversial 2022 retrospective, Philip Guston Now. Kentridge’s art, like Guston’s, is socially conscious, intensely autobiographical, and informed by a strong sense of justice, as embodied by his parents, both of them barristers who represented victims of South Africa’s apartheid system. (Kentridge’s father Sydney led the 1978 inquest into the torture and murder of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko.) Like Guston, Kentridge was born into a Jewish family, and satirical, and often terrifying figurative symbols of white supremacy populate each artists’ work. There are Guston’s notorious Klansmen, cartoonish hooded figures Kentridge himself traces back to Giorgio de Chirico’s surreal images of mannequin heads tightly wrapped in white, stitched fabric, which certainly alluded to Guston’s childhood in Los Angeles in 1919, a time when the city was an incubator and haven for the Ku Klux Klan. Meanwhile, Kentridge’s Soho Eckstein, a recurring charcoal-rendered character inspired in part by Kentridge's paternal grandfather Morris, has evolved over the years from an obvious symbol of colonial brutality and industrial greed, to someone a bit wearier and more confused, a stuffed suit bearing witness to the benefits of white privilege.

Also like Guston, Kentridge possesses a deep knowledge of the whole of Western art, and the sheer range of works on display is a lot for the average museum-goer to take in; from Duchampian constructions that include three Singer sewing machines, each fitted with an external megaphone and timed to “sing” a prerecorded, very South African-sounding anthem; to several hours’ worth of hand-drawn, stop-animation films; to small, black bronze sculptures looking very much like shadows cast as 3D reliefs.

But the MFAH’s thoughtful and (mostly) chronological installation gives the viewer plenty of space and time to take in Kentridge’s oeuvre and learn more about complex history of Johannesburg, a city he loves and adamantly refuses to abandon.

William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows is on view through Sept. 10.