Well Versed

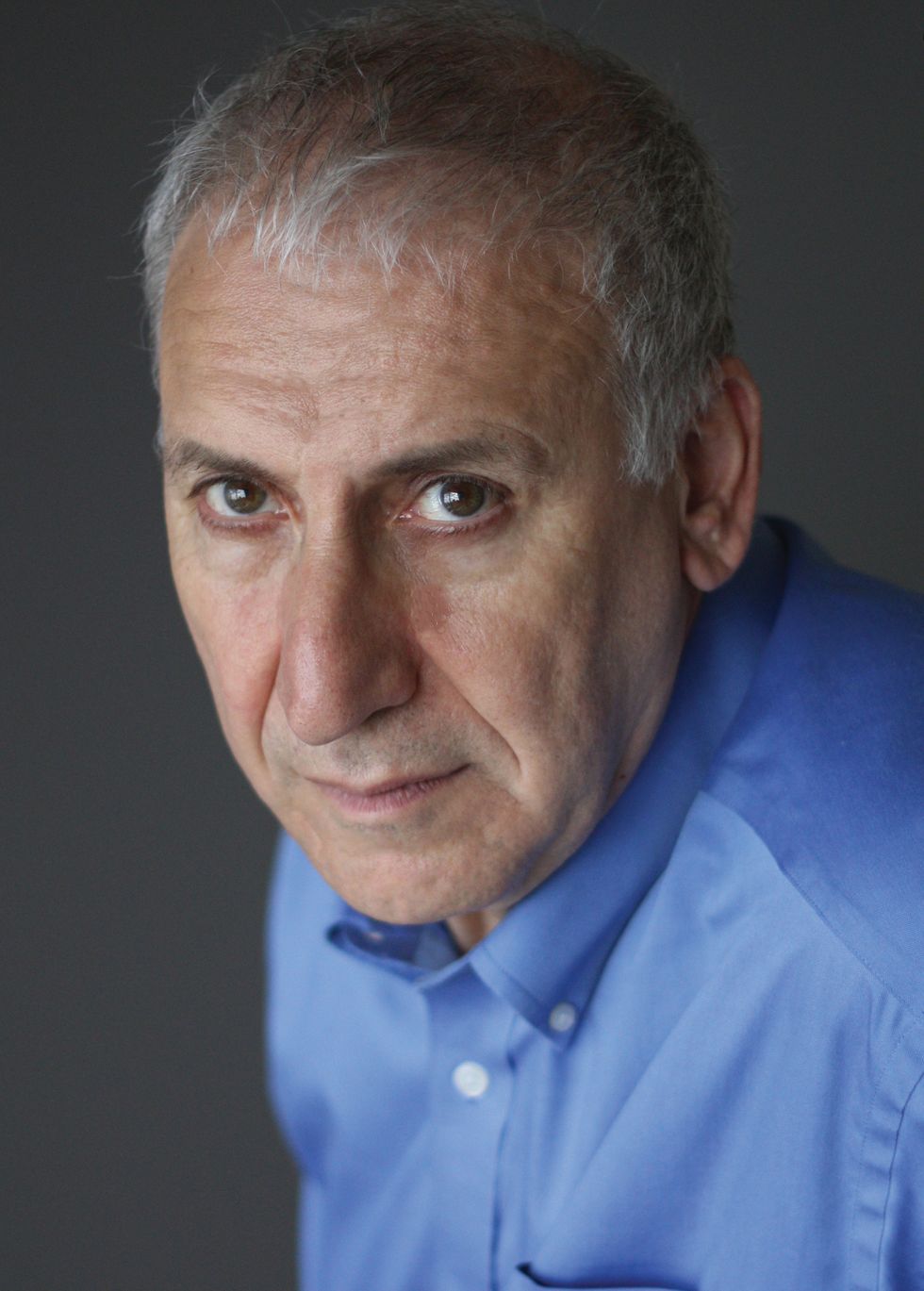

Prolific poet Edward Hirsch, once a popular UH professor, shares his pain, progress and love for Houston in a new collection of poems.

In the history of the University of Houston creative writing program, there is perhaps no professor more revered than poet Edward Hirsch. Hirsch, now 70, was born in Chicago and came to Houston when he was 35 years old, half a lifetime ago. He arrived in 1985 from Detroit, where he’d been teaching at Wayne State University, and stayed for 17 years, until he was appointed president of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation in New York in 2002. “Houston was a good fit for me,” says Hirsch by phone from New York. “What you have in New York is an established cultural life. But in Houston, there is an eagerness and urge to create. This makes it an oddly good city for poetry.”

When he arrived, Hirsch was just publishing his second book, the National Book Critics Circle Award-winning Wild Gratitude, and considered the UH gig his first serious job. In the intervening years, he’s produced seven more books and has won numerous other awards for his poetry, from the Rome Prize to a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship.

Still, he may be most widely known for his 1999 book How to Read a Poet and Fall in Love with Poetry, which introduced generations of readers — and many Houstonians — to the art form. Hirsch credits local literary institution Inprint with the inspiration for that work of literary pedagogy. “It was the people who would come to the Inprint readings that helped me formulate my ideas, and turned me from being a writer for the initiated to one for the uninitiated.”

But like any life, Hirsch’s has its wounds and scars. Most notably is the one resulting from the unexpected death of his 22-year-old son in 2011. Grief consumed him for several years, and ultimately led to the creation a book-length elegy, which was published in 2014 and named for his son, Gabriel. Now, six years on, he’s produced another work, Stranger by Night, published in March. It also contains numerous elegies — to his son, as well as to lost friends, such as the poets Mark Strand and Phillip Levine, among others.

In the opening poem, “My Friends Don’t Get Buried,” he describes visiting the sites of friends’ scattered ashes, writing “I am a delinquent mourner/stepping on pinecones, forgetting to pray/But the mourning goes on anyway/because my friends keep dying/without a schedule.” In the title poem, “Stranger by Night,” which is a reference to Hirsch’s declining eyesight, he writes, “After I lost/my peripheral vision/I started getting sideswiped by pedestrians cutting in front of me almost randomly/like memories/I couldn’t see coming.”

Remarking on the new book, Hirsch says it represents “a kind of spiritual arc” that that carries on from the previous work about his son.

There are several poems that look back in time to when Hirsch was himself a younger man, teaching poetry in coal country in Pennsylvania, or working on the railroad or living in Detroit. Houston, too, makes an appearance in the form of “Let’s Go Down to the Bayou,” a poem about how writing can serve as a secular sacrament. Houston is also name-checked in several other poems.

“[The book] is, ultimately, a celebration of all the things that have been meaningful to me,” he says. “It’s an intense look backward at what is sustaining to me.”

As for Hirsch’s legacy, it will be exemplified in both his own works and the scores of poets he taught and influenced over his long career, many of them in Houston.

“The city came as surprise to many of the poets who came to study in Houston, be they from Greece and China, San Francisco or Portland,” says Hirsch, adding, “I was born working-class in Chicago and, if there is one thing I can recognize about Houston, it is this: Its raw energy makes it truly an American place.”

Two poems in Hirsch’s new collection homage Houston.

Let’s Go Down to the Bayou

Let’s go down to the bayou

and cast our sins

into the brown water

on little strips of paper

slowly floating uphill

that way we did that fall

when we moved to Houston

and lived with a small

anonymity

in a large complex

set up for the families

of patients treated

for months

in a nearby hospital

because maybe this time

our neighbor’s daughter

with the shaved head

will be healed

and the bayou will accept

our murky sins

the way God never did

and cleanse us.

The Task

You never expected

to spend so many hours

staring down an empty sheet

of lined paper

in the harsh inner light

of an all-night diner,

ruining your heart

over mug after mug

of bitter coffee

and reading Meister Eckhart

or St. John of the Cross

or some other mystic

of nothingness

in a brightly colored booth

next to a window

looking out

at a deserted off-ramp

or unfinished bridge

or garishly lit parking lot

backing up

on detroit or houston

or some other city

forsaken at three a.m.

with loners

and insomniacs

facing the darkness

of an interminable night

that stretched into months

and years.