After Cardiac Procedure, Patient Reflects on Med Center’s Daring Heart History with Pioneering Doc

AS A LONGTIME Houston journalist, I’ve been trained to be impressed by the Texas Medical Center and its history. It’s the largest complex of its kind in the world, a leader in research in cancer, heart disease and more. It has several major hospitals and multiple medical schools, employs 100,000 people and treats 10 million patients a year. That’s all in the brochure.

But, over the summer, my interest shifted from merely professional to very personal. For the first time, after having lived nearby and having written about the Med Center for nearly 20 years, I became a patient there. I had heart surgery. Well, a heart procedure, a so-called ablation to correct a troublesome arrhythmia called atrial fibrillation.

Anyway, with a newfound fascination in the topic, I was thrilled to visit with pioneering heart surgeon and medical-device inventor Bud Frazier when we shot him at The Texas Heart Institute in the Medical Center for our 2023 Leaders & Legends portrait series. In talking with him, I was intrigued, of course, with all his many firsts and milestones — but mostly I was moved by his stories of the early days, and how he still remembers one patient from nearly 60 years ago. An Italian boy.

It was 1966, and O.H. “Bud” Frazier was a med student at Baylor. He’d stumbled into a specialty in cardiovascular surgery when a buddy of his roped him into helping with a research project on what at the time must’ve seemed like science fiction: the artificial heart. His teacher was the famous — and famously hard to please — Michael DeBakey, regarded as one of the greats in the field. “He was so mean and so tough,” Frazier tells me. “I wish he’d had a little more of the milk of human kindness.”

For decades, Frazier himself has been one the world’s leading figures in heart surgery, having invented and implanted multiple types of heart pumps and artificial hearts, not to mention having presided over more heart transplants than anyone else on the planet. But he was just 25 when he was tasked with “working up” a 19-year-old Italian man before DeBakey performed an aortic valve repair.

“The boy was so happy to be getting his heart fixed,” recalls Frazier, who, now 83, still keeps a windowless office filled to the brim with rare books at the Institute. “His mother was there with him. He was going to be able to do so much, was going to be an engineer.”

But things didn’t go as hoped. The patient went into cardiac arrest on the operating table. Frazier, just a few years older than the patient at the time, stepped in to keep him alive as long as possible. “I was young and strong, and I could massage his heart. I did this while he was awake.”

The Italian boy died decades ago with his heart in Frazier’s hand; the doctor still remembers every detail. (He remembers details about all the patients — especially the kids — lost under his care, and he still glances at the floor and speaks in hushed tones when he talks about them. His story about the five-year-old redheaded girl who died the same morning as two other children in high-risk procedures is a real heartbreaker; that day, Frazier says he fell apart and had to read St. Paul in the hospital chapel a while “to get my wits about me” before going back to rounds.)

But, even among such tales of drama and tragedy, the story of the Italian boy was unique in its impact. “I remember thinking, if my hand could keep him alive, there ought to be a pump that could do it,” he says.

And so began Frazier’s lifelong passion, which was reaffirmed a few years later after he was drafted into Vietnam as an Army surgeon, flying highly dangerous missions with soldiers aboard attack helicopters. “I really couldn’t do much for anybody under those circumstances, but they said having a doctor there was for the ‘morale of the troops.’ I told them, if it was for the ‘morale of the troops,’ get Sophia Loren,” he says with a chuckle, before returning to a more serious aura. “I was lucky to get out of Vietnam alive. So I decided to work with these pumps, to try to do something that might make a difference for people.”

The young doctor went on to be further mentored by Denton Cooley, beloved founder of The Texas Heart Institute and the first surgeon to implant a total artificial heart. He compares the “very gentle” Cooley’s skills to Lindbergh crossing the Atlantic using only a compass. “Nobody could do what Cooley did,” he says.

A moment with renowned heart surgeon Bud Frazier

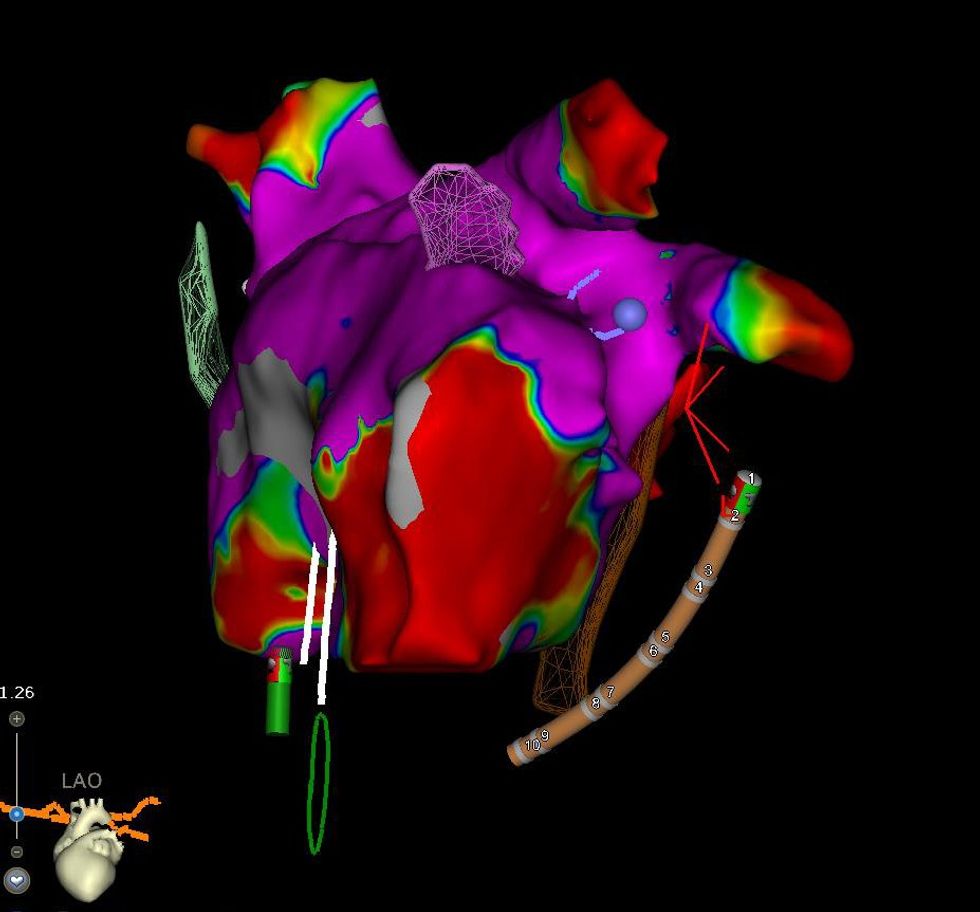

A 3D image of our author’s heart

Frazier has written many important chapters in the long, profound story of cardiac surgery in the Texas Medical Center. And it’s kind of wild that, as a patient, I can now add a pithy line or two myself.

My ablation procedure seems like Star Trek stuff compared to the early days of DeBakey, Cooley and Frazier. (In the Institute’s beautiful atrium of a museum, Dr. Bud shows me a makeshift blood oxygenator made from a coffeepot, from an era in which Med Center docs often built surgical devices themselves using whatever they could find, on their own dime, never giving a second thought to patents or pay-outs.)

In my case, in a hospital a few blocks from Texas Heart Institute, electrophysiologist Brian Greet — an extra-specialized kind of cardiologist who did part of his training at the Institute, where staffers are proud to point out he’s an alum — utilized remarkably advanced technology. No retrofitted Mr. Coffee’s in sight!

Without opening my chest, and using only minimally invasive small tubes called catheters — the room where this happens looks a lot like an O.R. when you’re wheeled in there on a gurney, but they insist it’s called a “cath lab” — Greet accessed my heart via blood vessels in my groin. Once inside, he used an imaging device called CARTO, proffered by Johnson & Johnson’s sprightly Biosense Webster team in Houston, to make a colorful, real-time 3D “map” of my heart.

Working from these images on large monitors, Greet, using another catheter outfitted with a heating element, then burned the heart tissue that appeared to have been causing the a-fib. He ablated it, is what he did. He emailed me the CARTO images that night, as I was home resting after my day trip to the hospital.

For his part, Frazier isn’t quite as impressed by the whizbang tech as I am. “I’m amazed by the advances,” he says. “To some degree. But technology comes on the backs of the pioneers, the people who were creative, who did something that hadn’t been done before. If you fail, everybody calls you an idiot. And if you succeed, everybody else tries to take as much credit for it as they can.”

One thing Frazier and I do agree on is how special Houston is, as a place for discovery. He likens the spirit of exploration and risk-taking in medicine to the wildcatters who got rich going for broke in the oil patch. “In Houston, you could do something and get away with it,” he says.

It also helps that many of those wildcatters became generous philanthropists, funding the development of a cutting-edge medical enclave that would become the perfect milieu for research — growing fast and bold, with little red tape. “They didn’t have restrictions.”

As my time with Frazier winds down, I take his parting words to heart. Pun absolutely intended. “A lot of the advances in cardiac surgery occurred here, in this Medical Center,” he says. “Not at Harvard or Princeton or Yale. They didn’t do it. I think it was done here because you could do things, and if it failed, you could try again. I don’t think it could have been done anywhere but Texas — and in Texas I don’t think it could have been done anywhere but Houston.”