The Godfather

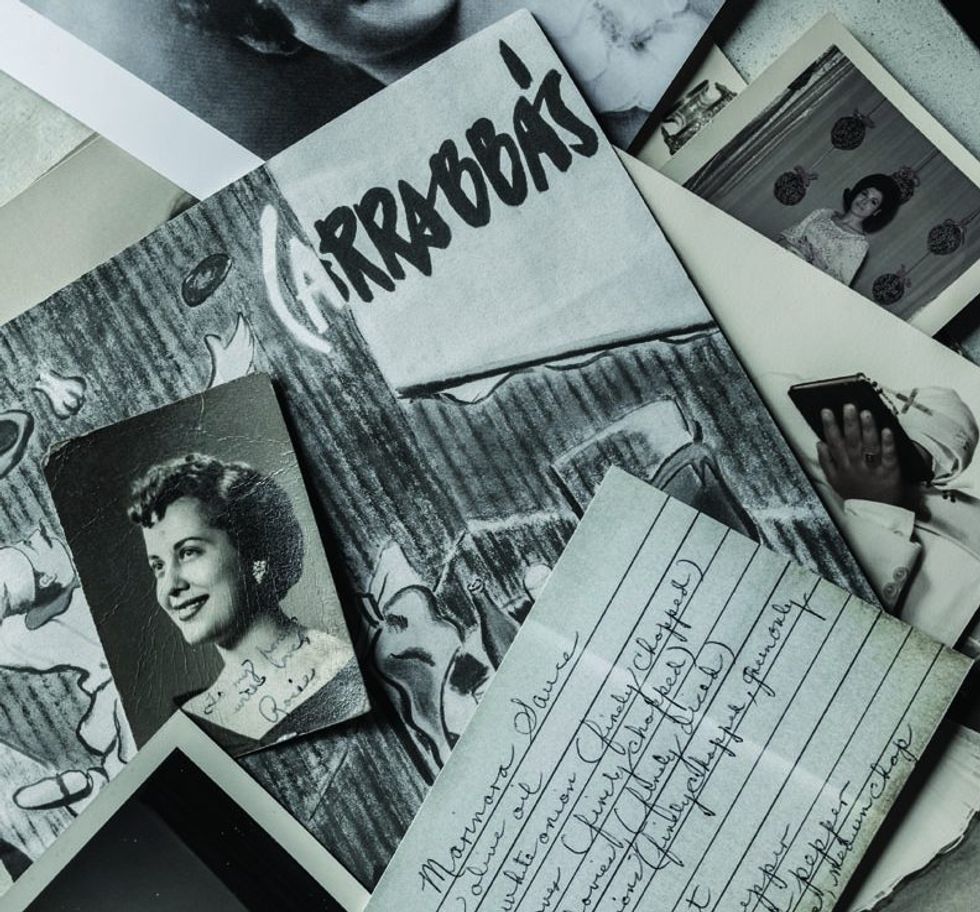

In a beautiful new memoir/cookbook, one of the city’s standard-bearers of Italian cuisine — and family tradition — tells all.

A descendant of Sicilians and a member of the city’s largest and most storied intermingling of food families, restaurateur Johnny Carrabba’s culinary journey began in Corleone — yes, that Corleone — and wound its way through his famous uncles’ kitchens and to the heights of Houston’s food scene. His empire grew to more than 250 eateries worldwide, before he came “back home” to his two original Carrabba’s Italian restaurants on Kirby and Voss, plus Grace’s and Mia’s Table, named after his grandmother and daughter respectively — and Common Bond Café and Bakery, which he co-owns. Now, with help from editors Roni Atnipp and Doug Williams, he’s sharing his best stories and recipes in a new book, With Gratitude, Johnny Carrabba, hitting shelves now. The following is an excerpt.

Mine is a story of immigrants, and fate, and coming home.

In Italy, around the turn of the 20th century, small farmers like my family faced considerable economic pressure. There wasn’t much land to work, and what little there was there was increasingly unproductive. It was tough to make an honest profit. So they did what many Europeans of that generation did: They looked west, to America, the land of opportunity.

My grandpa Tony Mandola’s parents left Sicily and came through Galveston before settling in the Dickinson area, where they were strawberry farmers. My grandmother Grace Testa Mandola’s family was also from Sicily and arrived in Houston by way of New Orleans and other parts of Louisiana. On the Carrabba side of my family, both my great-grandmother and great-grandfather came from a little Sicilian town called Corleone. (Yes, it was the same one immortalized — and fictionalized — in The Godfather movies.) They entered the country in Galveston and found their way to the Brazos River Bottom in Bryan, Texas, where they farmed cotton.

The hardships they all faced getting here are still unimaginable to me. They probably left Italy with three or four dollars in their pockets. They didn’t sail across the Atlantic on the Queen Mary; they were in the lower decks of cargo ships. Disease was rampant. Loved ones were left behind.

Eventually, however, everyone ended up in Houston. My grandpa John Carrabba got tired of picking cotton — he once told my grandmother, “Don’t ever buy me a cotton shirt again.” So he got out of the fields and onto the roads, delivering soda water on a truck. Over time, he saved up some money and opened a grocery store in Houston’s Fifth Ward in 1940. True to his Sicilian heritage, he worked hard to make his little business a success, and he did, eventually selling it and starting another one: Carrabba’s Friendly Grocery.

For their part, sadly, the Mandolas were no strangers to misfortune. My grandmother’s father, like my grandpa Tony, was a really good businessman who owned a profitable company in Alexandria, La., Testa Cola Bottling. But a bad fire swept through the plant one day in 1926, and he lost everything. Grandpa Tony was also very successful, the owner of a meatpacking house in Houston, Grade A Packing. He was just doing fantastic until he was in a bad car wreck in 1948. It put him in a coma for a long time, and he lost his business, too.

But being who we were, good people who had faced challenges and heartbreak without letting them get the best of us, we all continued to pursue the dreams that had originally brought my family to America. My mother and grandmother pretty much ran the grocery stores for the men — another lesson learned is that strong women are key to the success of a small family business — and I worked there after school and on weekends myself.

Meanwhile, my uncle Tony Mandola was working for the Rio Grande Tortilla Co., which was owned by Ninfa Rodriguez Laurenzo — known affectionately as Mama Ninfa — and her husband. As it happened, Uncle Tony was also dating the Laurenzos’ daughter, Phyllis, whom he later married. After Ninfa’s husband died unexpectedly, leaving her a widow with five children, she decided a restaurant would be easier to manage than a tortilla factory; she opened the original Ninfa’s on Navigation in 1973, and Uncle Tony went to work with her.

That put a whole lot of wheels in motion. Inspired by Uncle Tony, my Uncle Damian opened a restaurant in Huntsville. Uncle Tony left Ninfa’s and started Nino’s with my Uncle Vincent, and eventually went out on his own to open Tony Mandola’s Blue Oyster Bar on the Gulf Freeway. Damian opened a second Damian’s, this one in downtown Houston. Everybody, it seemed, was getting into the business — everybody except me.

I was going to college at the time and wasn’t much of a student. To make ends meet, I coached part-time at my old high school, St. Thomas, and picked up odd jobs from my uncles. Vincent would call from Nino’s saying his bartender had just quit and ask me to fill in. Or Uncle Tony would say he needed a waiter at Blue Oyster.

One Friday while I was waiting tables for Uncle Tony, he came in and said he’d just signed a lease for a second location on Shepherd Drive. I was happy for him, even though I had no idea what signing a lease meant. Then he dropped a bombshell: “Johnny, I want you to be my general manager. I need family over there.”

Well, I agreed and started operating the place as if it was my own. I didn’t have the experience or knowledge that my uncles had, so I just kind of fell back on instinct and ran the restaurant in much the same way my parents ran their grocery store. I liked it, too — the hard work, the long hours, the feeling of responsibility. After a less-than-successful college career, it felt like I’d found my place in the world. And the world was about to get bigger.

One night during the oil crash of the mid-1980s, Uncle Damian stopped by the Blue Oyster Bar to have dinner with me. Nothing fancy, just a quiet meal before he went home to his family. He had just returned from New York and told me all about the city’s casual, wood-burning pizza joints. “Would you want to do something like that with me?”

I was blown away and really flattered. I gave it some thought, and decided I was with him. We didn’t waste much time moving forward. Or trying to. We applied for a loan from the same banker my family had done business with for year. It felt like a sure thing. We gave him our pitch — we were confident, maybe even cocky — and waited for him to give us a check. But instead he gave us some pretty harsh advice.

“Johnny,” he said, “I’ve known you since you were born, but I can’t let you do this. It’s the worst economy in the city’s history, and you want to open a restaurant? Don’t do it.” I have to tell you, Italian boys can’t handle rejection very well. I got a little testy and walked out, thinking that he wasn’t the only bank in town. Eventually, 10 banks turned us down. Luckily, he 11th said yes, provided that we come up with $100,000 in collateral. Damian suggested I talk to my dad. In the tradition of all great Sicilian deals, we met him at his family’s house, at the dining room table, on Christmas Day 1986. We laid out the idea to him, and all he said was, “Yep, I can do that for you.”

Carrabba’s opened the next day, on Kirby near River Oaks, in a building that once housed an adult bookstore. The most expensive thing on the menu was a $9.95 T-bone steak. The priciest glass of wine was $2.25.

It was like lightning in a bottle. Pasta in bowls, good portions at moderate prices. Plus, a lot of people had never seen a woodburning pizza oven, and the open kitchen made them feel like they were at home. Other menu items included Grandma Carrabba’s artichokes stuffed with breadcrumbs, grilled Cornish hen salad, and pancetta-wrapped quail Marsala served over grilled polenta.

We were suddenly the hot spot. Even the beautiful people started coming. I’d never seen leather pants until then. One day, about a year after we opened, Damian called me with a plan. “Johnny, I think this Carrabba’s thing really has legs. It can travel.”

As in open another location? I was already sleep-deprived, working 18-hour days, seven days a week. I was the only guy with keys to the restaurant. And he’s talking about expansion?

People of Sicilian lineage tend to imagine they’re going to run one little business — a shoe shop, a grocery store, a butcher shop, a produce stand — and give it all they’ve got. That’s the way we’re raised. I figured Carrabba’s on Kirby was going to be my shop for the rest of my life, and when the time came to retire, I’d just hand it off to my kids, which, I didn’t even have yet. But Damian being Damian, he persuaded me to call a realtor, and I reluctantly reached out to Ed Wulfe, who’s a pretty big player in that business.

I told him Damian wanted me to look for a second location. He said to give him two weeks to find the perfect spot. An hour later, he called me back. “I have the perfect location for you — the corner of Voss and Woodway.” Five restaurants had gone broke there in 13 years. But Ed had a good feeling about it. “If you look at the neighborhood, and you run it the way you run Carrabba’s, it’ll be a slam dunk.”

So we started making plans. I called my mother, Rosie. She and Dad had just retired from the grocery store, and they were both still pretty young. I told her about the new location. “If you don’t mind,” I said, “I really could use you there a couple of hours a week to greet people, kiss babies, that kind of thing.” That was nearly 30 years ago, and Mom is there seven days a week, loving every minute of it.

After the Carrabba’s at Voss took off, the phone calls started coming in. People looked at what we’d done at Kirby, then with the second location, and, boy, did they see an opportunity. For my part, I was perfectly happy to stay small, and I told everyone so. Then one day Tim Gannon, a founder of Outback Steakhouse, called. He said he and his partner were interested in Carrabba’s. I still wasn’t having it, but that’s when fate stepped in again.

Tim had once lived in a garage apartment on Sunset Boulevard, not far from Carrabba’s on Kirby, and often came to the restaurant. He liked the food, the energy, the people, and the culture, and the experience had stayed with him. I couldn’t deny the sense that his interest in my restaurants was no accident.

We entered into a joint venture in less than 24 hours. For a couple of kids who got rejected by 10 banks, it was a pretty huge thing for Uncle Damian and me.

Eventually, Damian and I retained ownership of the two original restaurants, and a separate president ran the chain restaurants while we stayed involved in the franchise business. After a while, I left the corporate world altogether. As good as Outback was to us, I’m not really built for the corporate environment. I still see myself as the operator of a small business, running a familyowned restaurant. It’s where I belong. It’s what I was meant to do.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m really proud that a Carrabba’s grew to 250 locations. But I wanted to come back home. I found my way, too. And I couldn’t be happier that I did.