That’s a Rap

CAMH’s new show is screwed up — and that’s a good thing. Exhibiting work by a dozen artists, ‘Slowed and Throwed’ explores the connection between visual art and the late, great DJ Screw’s music technique.

When native Houstonian Patricia Restrepo returned to the city five years ago to work at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, she made a pilgrimage to Screwed Up Records & Tapes, the celebrated institution founded in 1998 by beloved music producer and community leader Robert Earl Davis Jr., a.k.a. DJ Screw. Restrepo had become increasingly aware of a connection between practices in contemporary visual art and Screw’s innovations in “chopped and screwed” music production.

This connection is explored in Slowed and Throwed: Records of the City Through Mutated Lenses (March 6-June 7), a wild and provocative group show curated by Restrepo, with guest curators Big Bubb, owner of Screwed Up Records & Tapes, and E.S.G., one of the original members of DJ Screw’s creative collective, the Screwed Up Click (S.U.C.). The show’s research advisors include Julie Grob, curator of the Houston Hip Hop Research Collection at UH, and Rocky Rockett, an independent hip-hop educator. With growing worldwide recognition of Houston as a hub for the development of jazz and hip-hop, the time is right for a museum to throw down and present a “visual arts interpretation” of one of the city’s most respected and influential figures in hip-hop.

The show’s name refers to two techniques DJ Screw used to create his immensely popular “Screwtapes” — cassettes he initially sold out of his home in South Park. After recording himself at the turntables, often accompanied by rapping from members of the S.U.C., he would slow down (or “screw”) the tape, completely transforming the key and mood of the track, so much so that the screwed version of Phil Collins’ 1982 hit “In the Air Tonight” sounds even more emotionally wrought than the original. “Throwed” or “chopped” refers to the repeated words and phrases Screw generated for poetic punctuation, using just two turntables and his formidable DJ skills to stop, start and otherwise “scratch” a second vinyl record against the first. Screwtapes were raw, experimental — and sounded damn good in your car.

“He had a thing about the sound and the quality,” explains E.S.G., who rapped on several Screwtapes. “It always had that deep bass in it. Still crystal clear, but Screw didn’t want any of that high-technology sound.” Screw completed hundreds of Screwtapes before he died in 2000 at the age of 27, and hundreds more have yet to be released.

“I am elated. I’ve been waiting on this moment,” says Rockett. “Our Screw community is very serious about his legacy. They will put you in check. But it’s okay to have a new appreciation for a different kind of art you never heard before.”

True to Restrepo’s vision, the 12 artists in Slowed and Throwed mirror different aspects of DJ Screw’s practice and history in surprising ways. For example, Jimmy Castillo photographs empty properties in the Northside neighborhood where he grew up and still lives, spaces where homes and businesses once stood, and uses the camera to capture repeated, translucent images of himself walking in circles, like a modern-day ghost dancer.

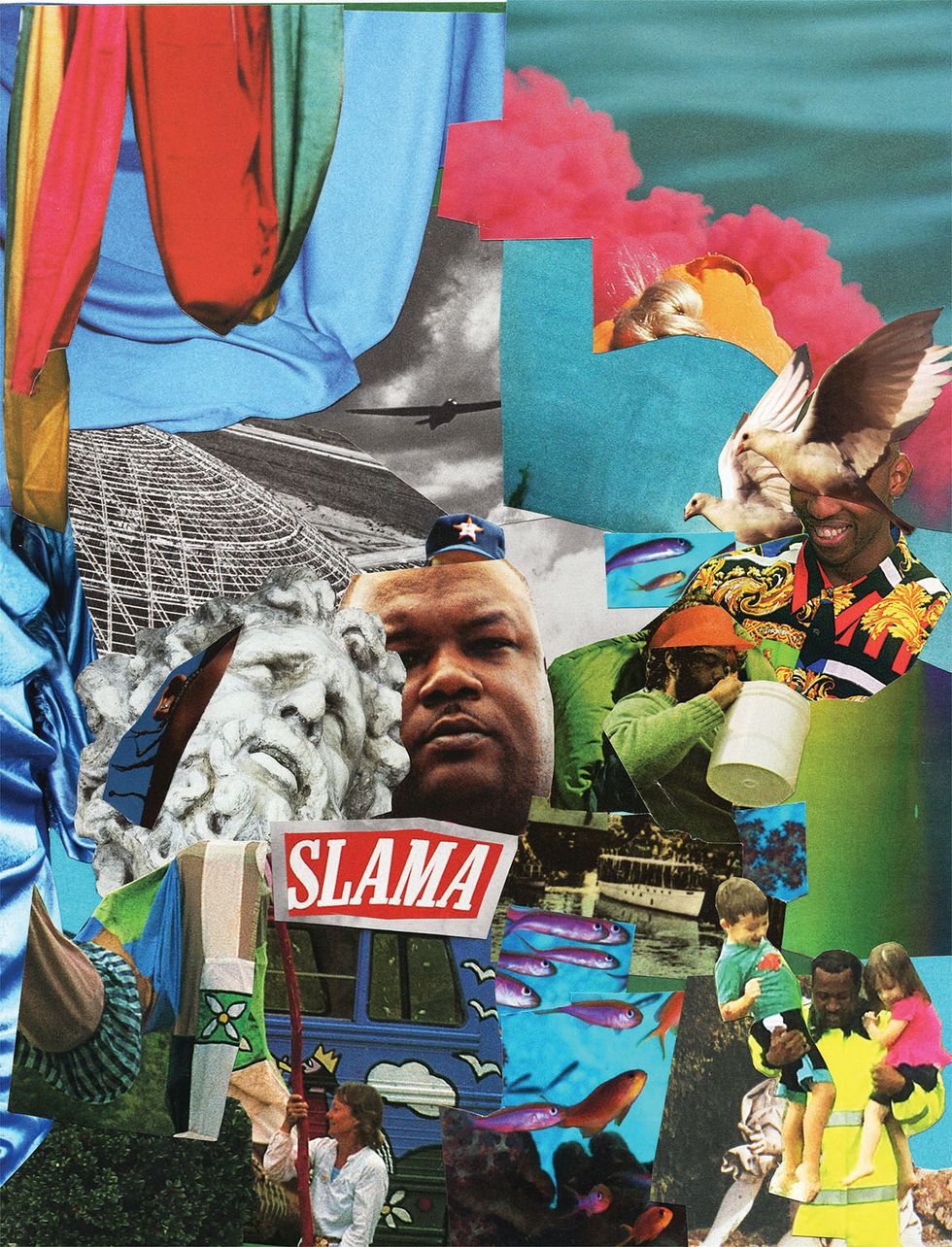

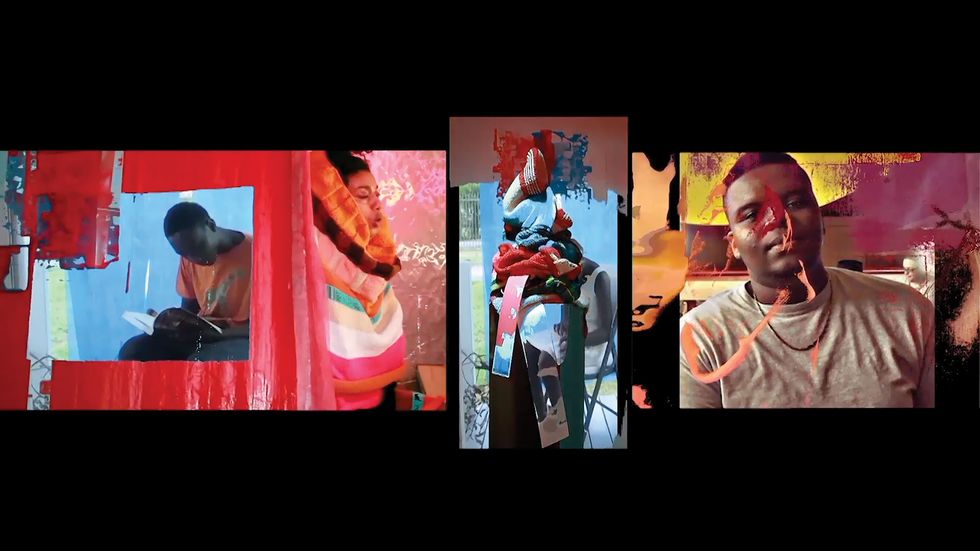

Meanwhile, Tay Butler, a former Milwaukee resident whose artistic practice was transformed upon relocating to Houston in his mid-30s, created two brand new works especially for Slowed and Throwed. Using images cut from magazines and other sources, Butler’s complex collages are a skeleton key to the history of a city he now calls home. “I think DJ Screw elicits so many potential readings,” says Restrepo. “You can really honor his practice by approaching it through many different lenses.”

“There’s still a mystery around how innovative and influential Screw was,” says E.S.G. about seeing his friend’s genius celebrated in a museum. “It would be a waste of creativity, a waste of work and history, if it wasn’t shown and highlighted.”

AT TOP: Karen Navarro’s ‘Twisted'