Retaking Shape

With a show bowing this month, octogenarian Harvey Bott channels a fascinating life story into fresh, pattern-savvy pieces that belie his senior status in the culture crowd.

Houston artist HJ Bott, better known by his friends as “Harvey,” gives a reporter friend a big smile when the two make eye contact in the parking lot at a River Oaks shopping center. Now in his 80s, he’s lost some hearing and walks slowly with a cane, but still radiates a defiant energy that has fueled a lifetime of making art.

“Your parking space says 30 minutes only,” the friend warns him, knowing they’re about to sit down for a long interview. Bott just grins. “That’s just to try and scare you,” he says conspiratorially. This, after all, is a man who survived the military, the New York gallery world, two previous marriages and a host of other escapades and adventures that would exhaust a seasoned memoirist. So why sweat this police-state crap? It’s time to talk about Thick and Thin and Back Again, Bott’s exhibition at Anya Tish Gallery of his ’70s-era monochrome series paintings alongside brand new wire sculptures, which is up April 21-May 27.

Born in 1933, Bott’s creativity was encouraged by his parents, as well as both sets of Ukrainian-refugee grandparents. Growing up on a farm in Gill, Colo., he became keenly aware of the visual power of lines and shapes in nature. “My paternal grandmother would make these big trays of soap,” says Bott, “and I would carve all of the animals on the farm, and make drawings of them. My grandfather used to do these elaborate drawings to plot the irrigation for farmers all over Colorado. The furrows became very important as a visual effect. He also had a woodworking shop, and let me use that as a little kid.”

Bott’s family eventually settled in San Antonio. During his high school years, he parlayed his drafting skills into providing precisely detailed architectural models for architects and builders. His formidable artistic skills have always gone hand-in-hand with an insatiable curiosity about the world. He turned down a scholarship to art school and instead joined the military. At the end of the Korean War, Bott went on to study cultural anthropology and hold down jobs as an industrial investigator and a member of the San Antonio police force, to name just a couple, all while continuing to make and show his art.

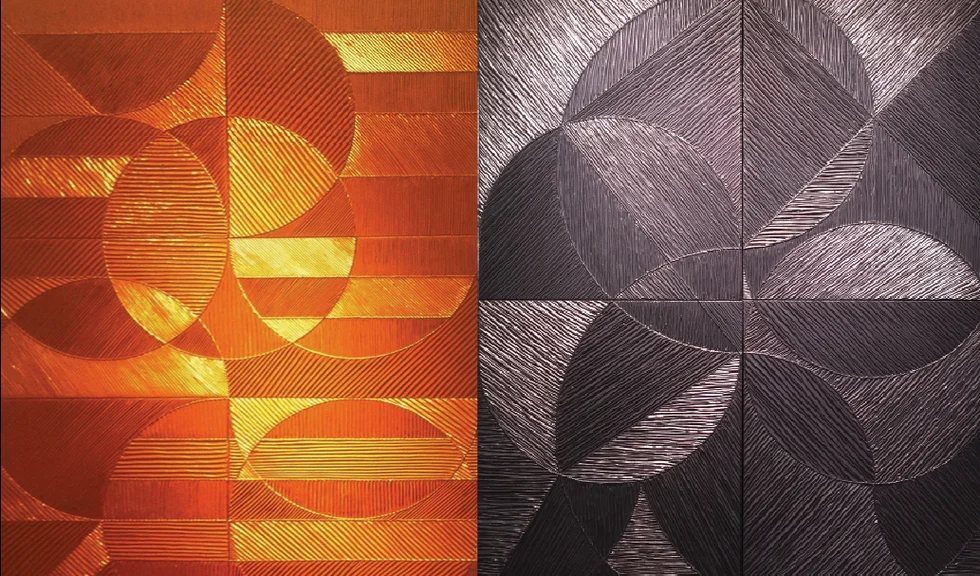

One fateful day — March 7, 1972, to be exact — Bott was doodling on a pad of graph paper during a business meeting at the UT med school in Galveston, where he worked as an assistant director of data processing. “I drew a square, quadrated it, and then drew an ‘S’ through it,” says Bott, “and I went, ‘Oh my God!’ The vice president for business affairs said, ‘Don’t mind Bott, he’s working on his art.’” What Bott had intuitively sketched turned out to be a self-contained collection of curved and straight lines simultaneously outlining several universal archetypes — such as the cross, yin-yang and fleur-de-lis — and could be recombined into countless variations to create two- and three-dimensional works of art. He was creating patterns and shapes within patterns and shapes, and it fascinated him. He quit his job and embarked on an artistic exploration that continues to this day.

In Bott’s monochrome series, his shapes are assembled like pieces of a primordial jigsaw puzzle, and filled with long slanted lines — or furrows — created with his fingers and a gooey combination of gel and paint. “Every one of the monochromes are titled after battlegrounds throughout history,” says Bott, whose role in the military was to use lined maps to guide artillery shells to their targets. Most of the monochromes in the show have never shown in Texas, and look as contemporary as anything being made by Houston’s current generation of upstart abstract painters.

But Bott has always been ahead of his time, even as he weathered more than a few personal and political storms. “Artists, writers and musicians get f***ed around by everybody,” he says with some weariness, recounting his and his now third wife’s move to Houston after being evicted from his Galveston studio by, he says, the local mafia. But when asked if he has any advice for young artists, who are discouraged by life’s ups and downs, he is surprisingly pragmatic.

“Just go with the flow,” says Bott. “Very often, when things are bad, there are also all kinds of new opportunities, and if you try to be resistant, you won’t see them.”