Arboretum's 'Enchanted' Evening Raises Half a Mil for Houston's Urban Oasis

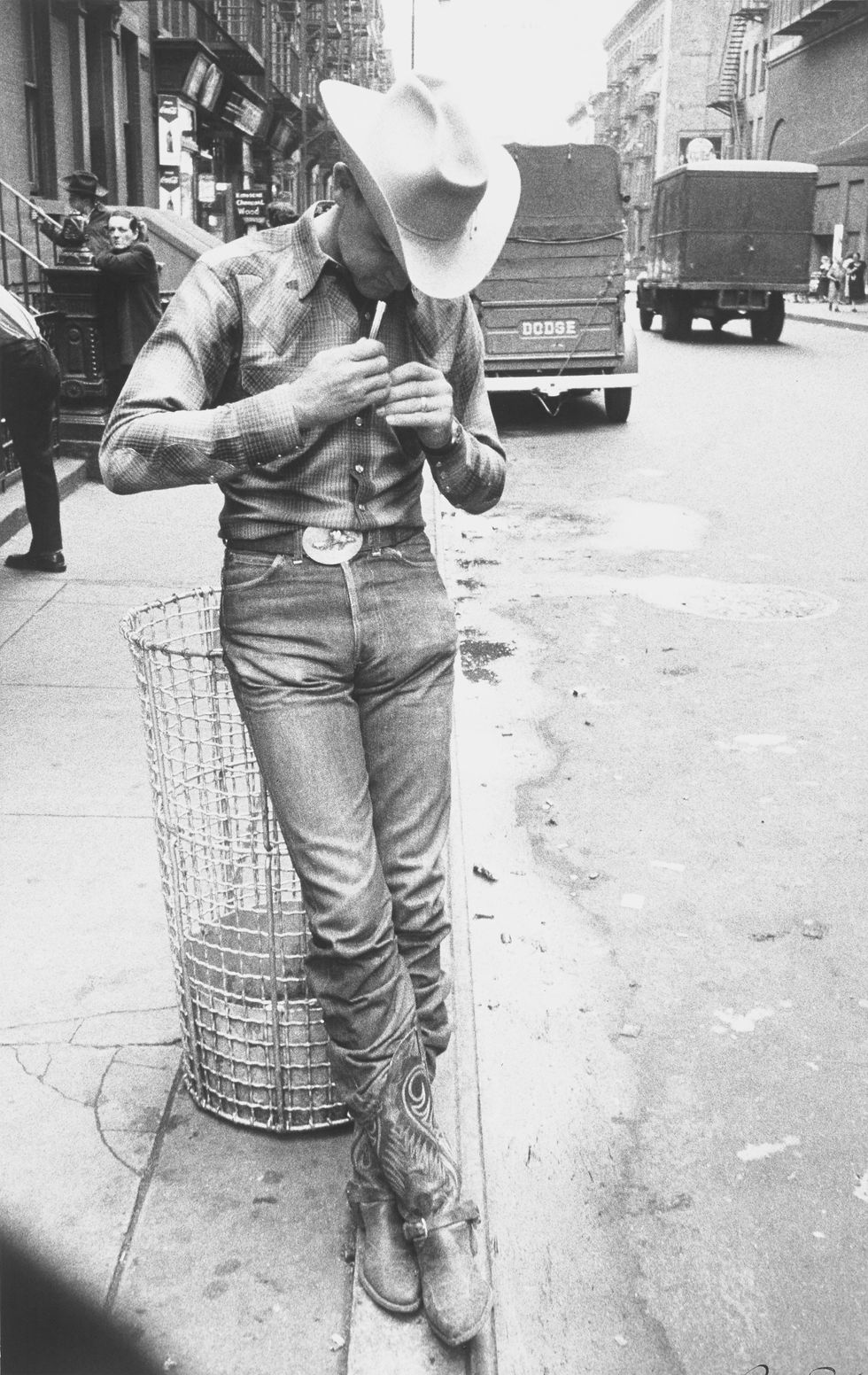

Robert & Amy Urquhart with Annie & Spencer Kerr

DURING APRIL'S STREAK of beautiful, breezy spring weather, the Houston Arboretum and Nature Center hosted its annual alfresco fete for 400.

The "Enchanted Forest" evening included dinner and dancing under the stars, but kicked off at dusk with fine wine and views of the Arboretum's spring wildflowers. Clad in floral-inspired attire, the galagoers descended upon the Nature Center courtyard and lawn, greeted by chairs Annie and Spencer Kerr and Amy and Robert Urquhart.

The crowd applauded honorees Marilyn and Harry Kirk, longtime supporters of the Arboretum and its improvement projects over the years, as well as of conservation and nature education in general. After dinner and the silent auction, Infinite Groove took to the stage, and the party continued well into the night. In all, more than $500,000 was raised at this year's gala.

Jason, Meredith and Allyson Kinzel

Steve and Betty Newton and Andrea and Bill White

Bobbi & Jonathan Worbington

Sam & Mary Sommers Pyne

Charles Reynolds & Kelley Stair

Chris and Therese Odell

Nancy Greig and Debbie Markey

David & Katherine Andrew and Kent & Kristen Bayazitoglu

Megan & Joe Keefe

Jason and Stephanie Beauvais

Frank and Amanda Hauser

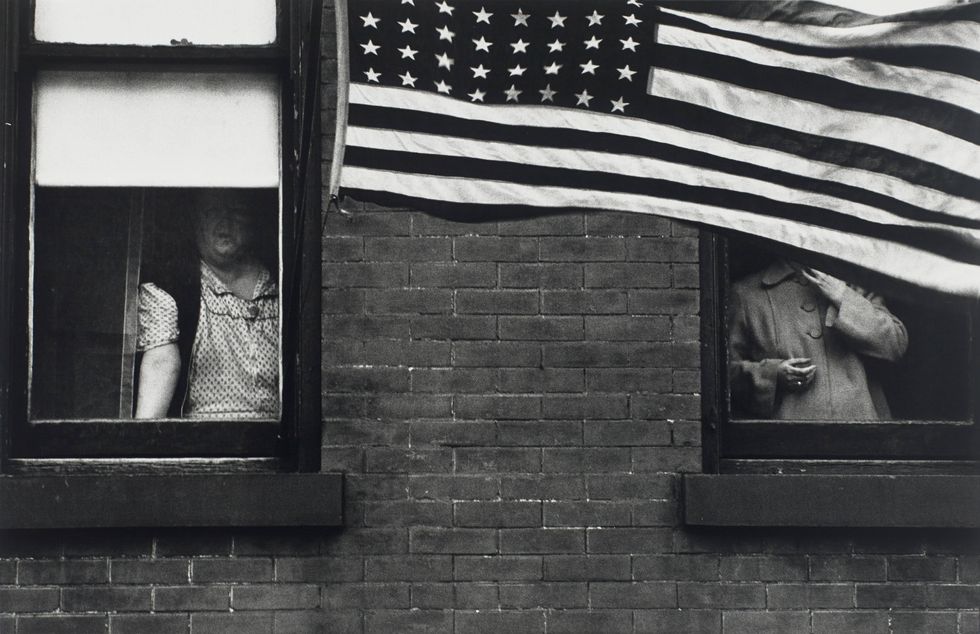

Marilyn & Harry Kirk

Leyton & Amy Woolf