In MFAH’s ‘Extraordinary Realities,’ Pakistani Painter and Glassell Alum Invites Viewers to Confront Biases

GIVEN PAKISTANI-BORN artist Shahzia Sikander’s deep connection to the city, it makes sense that the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston is the final stop for her retrospective, Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities. The critically acclaimed exhibit, which opened Sunday and is on view through June 5, is a visually sumptuous summation of 15 years of work by Sikander, whose art questions and subverts the viewer’s assumptions regarding ethnicity, gender and history. Interestingly, in several works, Sikander casts that critical eye upon herself, “the artist."

Using visual language uniquely attuned to sacred and secular storytelling, she reveals how her own preconceptions have changed over the course of her career, beginning as a young student at the National College of Arts in Lahore, to her arrival in the United States in 1993 to study at the Rhode Island School of Design and later, the Glassell School of Art, to her move to New York, where she currently lives and works.

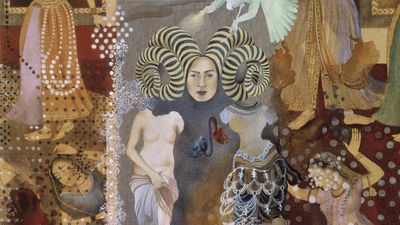

Sikander’s experiences in Houston and across the Southern United States had a profound impact on her work. In 1996, while a Core Fellow at the Glassell, she was invited to create an installation for Project Row Houses, the Third Ward-based non-profit organization and “social sculpture” founded in 1993 by Houston artists James Bettison, Bert Long, Jr., Jesse Lott, Rick Lowe, Floyd Newsum, Bert Samples, and George Smith. Sikander’s painting Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Beings (1989-97) is a constellation of images inspired by her time with Project Row Houses: There’s a row of shotgun houses and an upside-down portrait of Lowe, all later additions to what began as a rather benign image of a man reading a book. For Sikander, using erasure and overpainting to “violate” her work without knowing exactly what the end result would be is a visual representation of her own tightly held preconceptions being shattered and reconstructed.

'Intimacy' (2021)

'Hood's Red Rider No. 2' (1997)

'Eye-I-ing Those Armorial Bearings' (1989–97)

Complementing Sikander’s small-scale, detailed and symbolically charged paintings is an abstract, floor-to-ceiling work consisting of hanging layers of translucent paper; a couple of video animations; and, in its own room, Parallax (2013), an immersive 15-minute, three-channel animated film projected across a horizontal 45-foot screen. Composer Du Yun created the film’s score and sound design. In it, three poets recite and at times sing their words in classical and colloquial Arabic. (Regarding her paintings, Sikander has said, “I think of each work as a poem.”) Originally created for the Sharjah Biennial in 2013, Parallax takes the viewer on a dreamlike journey across the topography of the Strait of Hormuz, where the iconography of Sikander’s paintings, including severed human limbs and oil wells (also known as “Christmas trees”) float, congeal and explode, all to the accompaniment of Yun’s gently cacophonous score.

Like all of Sikander’s work, it’s both gorgeous and disturbing, and will definitely grab you.

- From Obama to Optical Illusions: Ambitious Spring Season Awaits at ... ›

- Far Out! '80s Bash and Art Auction Raises $500K for the Glassell School - Houston CityBook ›

- MFAH Supporters Keep it Weird at Annual Glassell Auction - Houston CityBook ›

- With Cool Abstract Collage Permanently Installed, Rick Lowe Is On the Map at UH - Houston CityBook ›

- MFAH Art School Kicks Off Series of Exhibits Celebrating Talent of its Staff - Houston CityBook ›